Modulation

Tonicization occurs when a chord or short succession of chords are borrowed from another key in order to emphasize—or tonicize—a chord in the home key. (See analyzing applied chords.) Modulation occurs when a longer succession of chords emphasizes a new tonic, leading to the perception of a new key. The principal difference between tonicization and modulation is the presence or absence of a cadence: tonicization does not incorporate a cadence in the tonicized key; modulation does incorporate at least one cadence (PAC, IAC, or HC) in a new key.

There are several ways in which a composer can effect a modulation. The most common are described below.

Direct/phrase modulation

A direct modulation occurs when a chord in the previous key is followed directly by a chord in the new key. In other words, there is no smooth transition or overlap between keys, just a direct movement from one key to the next. This often happens at phrase boundaries, with the old-key tonic ending one phrase and the new-key tonic beginning the next. When a direct modulation happens across a phrase boundary, it is also called a phrase modulation.

Examples of phrase modulations abound at the point between the end of the exposition in a minuet or a sonata and the beginning of the repeat of the exposition (if an exposition repeat is present).

A direct modulation is noted in a harmonic analysis by following the last chord in the old key with the new key, followed by a colon, and then the first chord in the new key.

G: I II V I Am: I . . .

or

G: T1 S4 D5 T1 Am: T1 . . .

Step-up/pump-up modulation

In the pop literature, direct modulations by whole- or half-step are common near the end of the song. Direct/phrase modulations by step from old-key tonic to new-key tonic in pop music are also called step-up or pump-up modulations. A step-up modulation is notated like a direct modulation.

“I Wanna Be Sedated” by the Ramones includes an obvious step-up modulation (1:10).

Truck-driver modulation

A truck-driver modulation is a direct modulation that moves from the old key (usually the tonic chord) to the dominant chord of the new key to prepare that tonic arrival, again common in pop music. The idea behind the name (coined by Walter Everett) is that the music loses energy briefly while in “neutral” (the new key dominant) before moving to a higher state of energy (the new-key tonic, a step above the old-key tonic). A truck-driver modulation is notated like a direct modulation.

Billy Ocean’s “Get Outta My Dreams” contains a classic truck-driver modulation (3:55).

Pivot-chord modulation

A pivot-chord modulation makes use of at least one chord that is native to both the old key and the new key. It is the most common type of modulation in common-practice tonal music. The smoothest type of pivot-chord modulation uses a pivot-chord that expresses the same function in both keys — commonly subdominant function, but other functional arrangements are possible and commonly used.

When a chord expresses dominant function in the new key and is an applied chord in the old key, it is not a pivot chord. Instead, that chord is effecting a direct or truck-driver modulation. A pivot chord must belong to the diatonic collection of both keys (keeping in mind that in minor, both la and le, and both ti and te are “native” to the minor key).

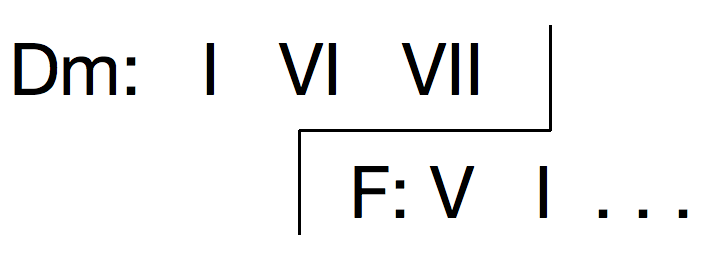

A pivot-chord modulation is notated in a special way. The pivot chord receives its analytical symbol for the old key, as usual. Below that symbol is the new key, colon, and the analytical symbol for the pivot chord in the new key. When using notation software, a two-layered analysis is fine: use the lyrics tool to create multiple “verses” of harmonic analysis, one for each key, overlapping on the pivot chord. When analyzing by hand, use a bracket like the one shown in the following example.